The US housing department’s ambitious initiatives of the 60s and 70s created urban communities that were both mixed race and mixed income. Though many didn’t last, are there lessons in them for Donald Trump’s new housing secretary?

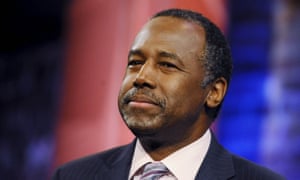

Innovation is, to put it mildly, not one of the first attributes that come to mind when you think of “Hud” – the US Department of Housing and Urban Development, soon to be overseen by Donald Trump’s former Republican rival Ben Carson. Yet this wasn’t always the case.

Imagine urban and suburban communities that banned cars, collected trash in pneumatic tubes, offered prototype community video chat capabilities, built elaborate pedestrian and cycle networks, and carefully retained existing foliage. You may not be thinking of the Jetsons, but products of the groundbreaking Hud New Towns initiatives in the late 1960s and early 70s.

What’s more, these aims were achieved while paying real and successful attention to creating both mixed-income and mixed-race communities.

So where should Carson go to be inspired by these pioneering projects? The catch is (with a few exceptions) federal support for them had sputtered by the mid-70s and vanished entirely in subsequent years, leaving at best, mere fragments of their once grand ideals.

The genuine problems with some of these projects – now perceived as failures, if recalled at all – eclipsed their admirable qualities in historical memory. These are qualities that might have offered Carson models for a country that is currently experiencing acute housing shortages in many of its metropolitan areas.

In the 70s, 15 projects were approved for “Title VII” support, most on greenfield sites near existing metropolitan areas. Two were in cities: Roosevelt Island (previously known as Welfare Island) in New York and Riverside Plaza in Minneapolis. Another, Soul City, was distant both from any nearby cities and prevailing practices of building them, as an effort to build a genuinely multi-racial community, spearheaded by an African American developer and African American architects.

There were many inventive elements on the drawing board, and some became a reality. If most developments were substantially suburban in character, planning mainly for single family homes, they often integrated higher density elements or multi-family homes, as well as significant efforts at pedestrian friendliness.

The Woodlands, near Houston, attracted praise for a trait that seems intuitive: retaining nature. Initial planning in semi-arid Texas was guided by an intention not to disturb the site’s water table, which would have affected the vegetation. The preservation of generous amounts of greenery around existing streams and drainage patterns was the first planning goal, not an afterthought.

Jonathan, Minnesota, a suburban new town, included an extensive trail system throughout the community and even more futuristic touches. According to Andy Sturdevant in the Minneapolis Post: “Each house was to be wired with interconnected cables as part of a General Electric Community Information Systems (CIS) project that would turn each television into a telephone that allowed you to communicate visually with your neighbours.”

Each home’s address was also its ID number for the system: “Someone dials up 110612 on their television, your TV makes a futuristic ringing sound, and you can have a video conversation,” Sturdevant wrote.

The two urban projects, Roosevelt Island and Riverside – both of which were fairly substantially realised – were thoughtful reactions against the known shortcomings of the design and composition of prior decades of low-income housing. Both forsook the anti-urban characteristics of prior decades of towers in the park and stressed the importance of planning for a mix of incomes.

Roosevelt Island (substantially the work of New York’s fascinating Urban Development Corporation) centred its marquee-architect designed main street around a coherent, colonnaded main street lined with shops. It introduced other innovations, banning private cars (for a while) and collecting trash via a pneumatic tube system.

Riverside Plaza, designed by the notable modernist Ralph Rapson, included Minneapolis’s first high-rise residential towers – but, more importantly, offered buildings at a variety of scales designed to house a variety of incomes, along with retail and community amenities. It was also a surprising television star, the site of Mary Tyler Moore’s residence in later seasons of the eponymous show.

How did this brave new wave of innovation come about? Two housing bills in the twilight of the Great Society sought to chart a brighter residential future in offering loan guarantees and other incentives to developers to build mixed-income and mixed-race modern towns. The latter bill, passed in 1970, formed a corporation chartered to distribute $500m in bond guarantees to new town projects.

Inspirations were quite openly European, yet the programme’s structure was considerably different. Congress eschewed the direct construction of new towns, as Nicholas Dagen Bloom, associate professor of social science at New York Institute of Technology, wrote in an 2001 essay entitled The Federal Icarus:

“Title VII stated instead that the government would ‘rely to the maximum extent on private enterprise’ in the creation of new towns. At heart, congressmen sought to harness the power of private enterprise for public policy, believing they could save the government money by recruiting developers who would, through their plans, attract home-buyers and their money. Title VII thus relied on the individual choices of thousands of homeowners who would, in theory, buy homes in these towns and in turn subsidize the high development costs of these communities.”

It was a forward-thinking solution, mandating the “substantial provision for housing within the means of persons of low and moderate income”. It also encouraged the use of design innovations in land use and construction, the provision of community services, and more. The carrot was federal loan guarantees and promises of eligibility for other financial support.

The developers were varied, ranging from Robert E Simon (creator of the well-known new town of Reston, Virginia) to Edmund Marcus (son of the Neiman Marcus department store founder) to Floyd McKissick (civil rights leader and head of the Congress for Racial Equality, who lead the Soul City project).

What could go wrong? Quite a lot, actually. Most Title VII projects didn’t advance very far. Some, such as Soul City, were too far away from existing population centres to attract much growth. Others were admirably set up but failed to attract buyers, probably due to their aversion to any or all of the characteristics of modern, mixed-race or mixed-income planning. Some developers didn’t manage their projects well; others suffered when pledged federal grants failed to materialise.

In time, the Carter and Reagan administrations terminated federal relationships with most of these projects. Some never really developed, while others ended up as conventional suburbs. Riverside Plaza fell from grace after its owners abandoned its original careful balance of income, and converted the complex entirely to subsidised housing.

And yet some things went very right. Roosevelt Island, which had been carefully designed and engineered for multiple incomes, remained a lasting success, with an unusually low crime rate even through the city’s most dangerous years, and a recent spurt of growth including a new Cornell Tech campus on the island’s south end. The Woodlands, too, flourished as both a high-end suburb and a corporate centre, although its lower-income elements essentially vanished.

Suburban new towns may seem quaint to foolhardy given 40 additional years of sprawl, yet there are traces of these ideas in the recent rise of New Urbanism and efforts to provide options beyond the car. Perhaps more importantly, the Title VII new towns were a large-scale effort to achieve income integration as a central goal of housing policy. Subsequent decades only rendered clearer the lesson that concentrated amounts of poverty tend to produce comparatively high concentrations of crime and little opportunity.

Today it’s not simply the poor, but a broader number of lower-income Americans who are increasingly squeezed by rising rental costs. A Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies report early last year found a remarkable growth of 9 million renters to 43 million from 2005 to 2015. These are increased numbers chasing a dwindling supply, leading to the unenviable situation of more than 28% of renters paying more than half of their gross income in rent. As with any shortage, lower-income Americans are most affected.

What’s the most important quality missing today? While barriers to construction continue to choke off the meaningful expansion of housing supply, government support for low-income housing typically remains minimal. There is also an element of self-fulfilling prophecy to much of their work: low-quality construction only sporadically maintained will inevitably age badly and produce undesirable results. The new towns movement wasn’t a panacea by any measure, but it demonstrated the notably superior results that slightly greater effort could produce.

The Trump administration has broadcast its enthusiasm for infrastructure spending – and there’s no structure more important to the public than a home. Ben Carson and the Department of Housing and Urban Development could do far worse than look to the spirit of experiment of the new towns movement. Today it’s not new towns but old ones under increased pressures of growth – but we need experiment and effort to make them generally accessible again.

Anthony Paletta writes about architecture and urbanism for The Wall Street Journal, Metropolis, Architectural Record and The Architects Newspaper. Follow Guardian Cities on Twitter and Facebook to join the discussion, and explore our archive here